Buddhist cosmology is one of the least explored and most fascinating aspects of this ancient tradition. Although interest in Buddhism today tends to focus on topics such as meditation, ethics and philosophy, the vision of the universe presented in Buddhist texts offers a rich narrative that connects the spiritual, the moral and the cosmic. In this interview, we talk with Óscar Carrera about his new book The Buddhist Universe: According to Early Sources, published by Editorial Kairós in 2024. Carrera shares his reflections on Buddhist cosmology, addressing the challenges of reconstructing such a complex vision from scattered sources. He also analyzes modern interpretations that tend to psychologize these ideas and reflects on the dialogue, or lack thereof, between Buddhist cosmology and contemporary science. Through his answers, the author invites us to look beyond modern simplifications to explore a universe that, though distant in time and culture, continues to offer profound lessons about the mind, morality and our relationship with the cosmos.

Óscar Carrera holds a degree in Philosophy from the University of Seville and a specialization in South Asian Studies from the University of Leiden. In his master's thesis he delved into the study of music and dance as reflected in the literature written in the Pali language. Throughout his career, he has published numerous articles in specialized journals on Buddhism and is the author of several works of fiction and essays, including The Nameless God and Human Mythology, which reflect his ability to combine intellectual rigor with narrative creativity. Committed to cultural dissemination, he is a regular contributor to Buddhistdoor en Español, where he writes articles and offers analysis on various aspects of Buddhism.

BUDDHISTDOOR EN ESPAÑOL: In your book you investigate and delve into Buddhist cosmology according to the Pali sources. What motivated you to explore this aspect of the tradition instead of other more usual topics, such as meditation or ethics?

One way to respond is that, from a historical perspective, these other issues do not seem to be as commonplace. It has long been debated whether there is an ethic in pre-modern Buddhism, i.e., a systematic moral reflection as opposed to a mere morality, recommendations and precepts that elude philosophical inquiry because they come from an enlightened authority. According to ethicist Damien Keown, we hardly find any treatises on ethics in classical Buddhism. If this is true, "ethics" in Buddhism is largely a modern offshoot: its moral rules in "our" field of moral reflection. What to say about meditation, an initiatory activity today promoted to a mass public through apps! Often another hybrid de-ritualized, conceptually secularized and psychologized as much as possible. I will add that in the Pali tradition, meditation manuals in the strict sense do not abound either. These and other cases indicate that part of what we call Buddhism today is a transplant of practices or concepts into the familiar terrain of modern worldviews, but I already know these and they are not the result of more than two millennia of Buddhism.

BDE: The cosmology you describe was systematized in a late period, although it is grounded in Pali speeches. What challenges did you encounter in reconstructing this view of the cosmos from scattered sources?

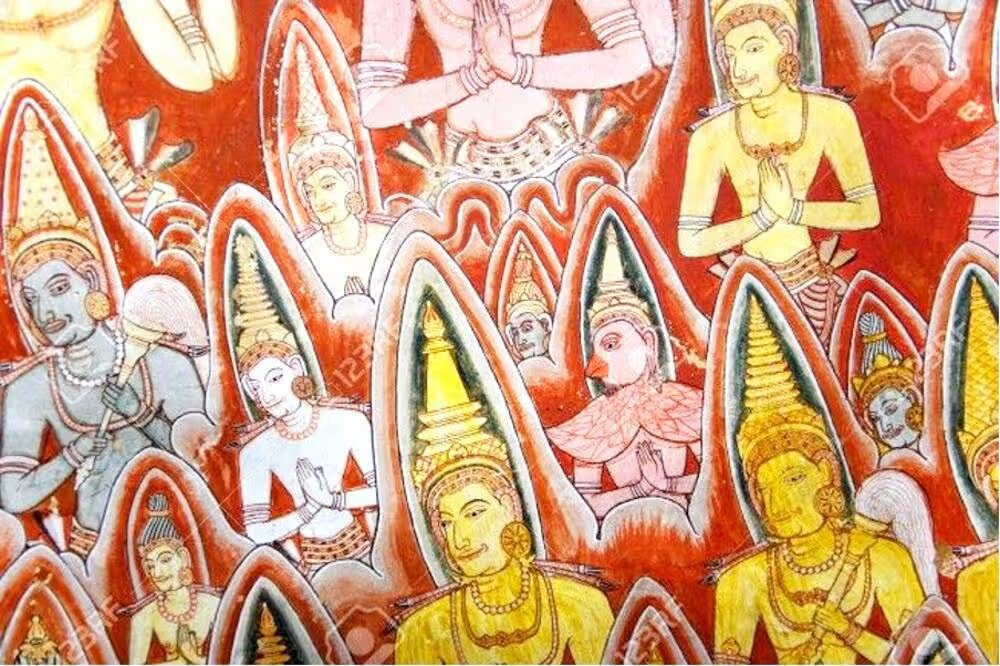

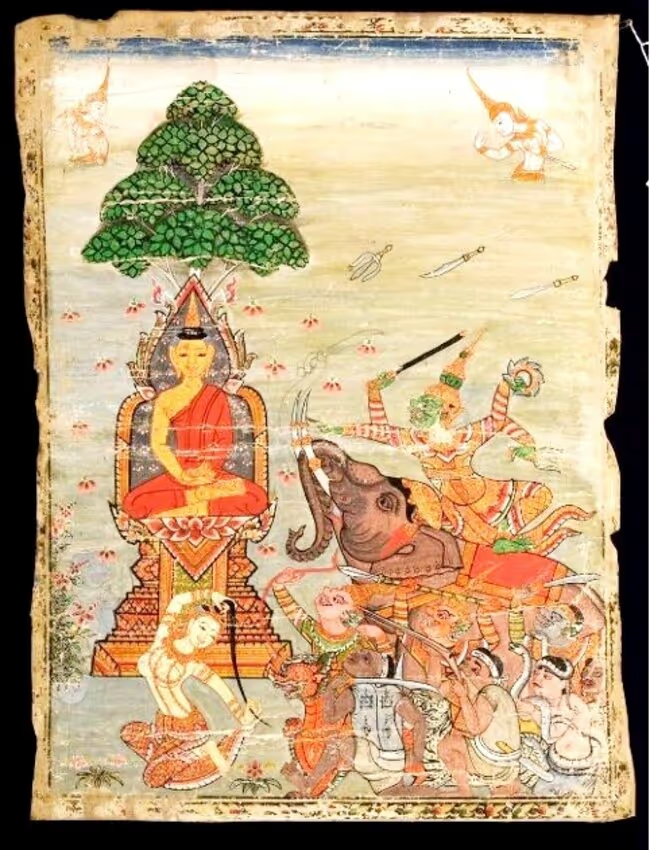

The texts employed, canonical and commentarial, are catastrophically plural, a chorus of dissonant voices; in this field of cosmology more than in others. The book attempts to contain tensions and present a polished surface, but this is only a pedagogical strategy. To give an example, in the most common characterization Erāvaṇa is a polycephalic elephant that serves as a ceremonial mount for Indra (Inda, Sakka): every good Indian deity has his mount and we can imagine Indra on his elephant, like the bodhisattva Samantabhadra, perhaps going to battle the titans(asura) on his formidable mount. But in the commentaries Erāvaṇa is described as a kaleidoscopic being, at the limits of imagination: he has thirty-three heads with seven tusks on each head, seven lakes on each tusk, seven plants on each lake, seven lotus flowers on each plant, seven petals on each flower, seven goddesses dancing on each petal... The gods are usually miles high; other times they are human height, and still others may congregate dozens on the tip of a needle. Our criteria of reality and representation dissolve into thin air when we approach the inhabitants of other planes of rebirth, and we find passages very conscious of this, while others are of a flatter realism.

BDE: We observe an interesting phenomenon in the contemporary dissemination of Buddhism: while the canonical texts present a rich cosmology with diverse planes of existence and supernatural elements that swarm the Buddhist universe, such as the asuras, the figure of Māra and the nagas, modern interpretation, especially in the West, focuses almost exclusively on its philosophical and meditative aspects. Do you consider that this transformation responds to a necessary adaptation to the contemporary world or represents a simplification that compromises the integral understanding of this tradition?

It is what it is: the creation of a new form of Buddhism that did not exist before and that would not have emerged from any other context of cultural exchange. A new hybrid and mestizo Buddhism, as are all regional and historical Buddhisms, although this one has to build longer bridges (as it enters into dialogue with currents such as scientific materialism or empiricist skepticism, antipodal to any previous Buddhist culture). In that labyrinth of mirrors we wander, sometimes very lost in our rhetoric, delighted by the sound of our own voice. Although my book is also guilty of cultural adaptations, which are intended to be conscious (for example, I underline elements of "magical realism" because I believe they will pique the reader's interest), I understand that the most rational move for someone who finds himself locked in a labyrinth is to try to get out. At least, to take the first step, which is to be quiet for a few moments: to try to silence the inherited worldview for a few moments.

BDE: Buddhist texts in the Theravāda tradition describe a correspondence between meditative states (including jhānas) and cosmological planes. How does this correspondence between inner experience and the structure of the universe illuminate the Buddhist understanding of consciousness and guide your meditative practice?

Correspondence offers a vast backdrop to the meditative experience, which reveals itself to be a crossroads between worlds: some meditative states are not experienced only in the human world, in that privacy or interiority with which we moderns endow the mind, but are a bridge to other worlds. By meditating we habituate ourselves to the "frequencies" of other planes of rebirth and this will influence the destiny after death, for the mind will leap into that which is of a similar nature. Anyway, I understand that mental states are transverse to the planes of rebirth: it is not that a certain absorption(jhāna) of a human meditator is only the mental reflection of certain heavens. Absorption is a fundamental reality accessible to various planes, but one that only in those heavens is the default state of mind; in planes that are "below" them, such as ours, it is difficult to obtain, and for those placed above in the celestial-meditative progression it is a trinket. I confess that it is difficult to pronounce on this ground because Buddhism, like other Indian schools, takes this mind-cosmos correspondence for granted and rarely states it explicitly; its contours and implications remain fuzzy.

BDE: Buddhist texts in the Theravāda tradition describe a correspondence between meditative states (including jhānas) and cosmological planes. How does this correspondence between inner experience and the structure of the universe illuminate the Buddhist understanding of consciousness and guide your meditative practice?

Correspondence offers a vast backdrop to the meditative experience, which reveals itself to be a crossroads between worlds: some meditative states are not experienced only in the human world, in that privacy or interiority with which we moderns endow the mind, but are a bridge to other worlds. By meditating we habituate ourselves to the "frequencies" of other planes of rebirth and this will influence the destiny after death, for the mind will leap into that which is of a similar nature. Anyway, I understand that mental states are transverse to the planes of rebirth: it is not that a certain absorption(jhāna) of a human meditator is only the mental reflection of certain heavens. Absorption is a fundamental reality accessible to various planes, but one that only in those heavens is the default state of mind; in planes that are "below" them, such as ours, it is difficult to obtain, and for those placed above in the celestial-meditative progression it is a trinket. I confess that it is difficult to pronounce on this ground because Buddhism, like other Indian schools, takes this mind-cosmos correspondence for granted and rarely states it explicitly; its contours and implications remain fuzzy.

BDE: In your book you describe a Buddhist universe that is intrinsically moral, where the actions of beings determine their place in the structure of the cosmos. How does this vision of an ethically ordered universe dialogue with the image offered to us by modern scientific cosmology? What challenges and opportunities does this difference present for contemporary Buddhist practitioners?

Depending on how you look at it, a fruitful dialogue can be established, or none at all. At the astronomical level it seems arduous: we are told that modern physics proposes an outer space empty of life and values, impossible to reconcile with the Buddhist vision of an overpopulated and moral universe. We have long sought links between Buddhism and physics or neuroscience, but I would argue that there is more potential in Darwinian biology, as it describes a process analogous to karma and rebirth. We sentient beings are the way we are because of the actions of our evolutionary ancestors, who have determined our psycho-physical structure down to the smallest detail. Sentient life arises, evolves and thrives through the greed(lobha) and aversion(dosa) of beings subjected to a process of selection of the survivors who manage to pass on their genes and, in many cases, prevail over their competitors. It is intriguing what it means, in this framework, that the Buddhist monk does not reproduce! He embraces a radical non-aggressiveness and renounces the sexual desire that is behind his birth as a human being, but also, in the longue durée, the fact that he has a head, a sternum, an opposable thumb... To introduce the concept of ignorance(moha) is more complicated by its religious or value nuance, but it is obvious that, from a Buddhist point of view, where aversion and greed, this fuel of sentient life, multiply, there is an ignorance that allows its indefinite continuity.

I think that Buddhism and science can dialogue and find deep affinities. Of course, if one examines the ancient Buddhist cosmology in detail, one will find flagrant ahistoricity, anthropocentrism, androcentrism (or outright misogyny), Indocentrism and even touches of casteism. It is a worldview created by humans for humans, but this, rather than being an objection to this particular cosmology, should make us reflect on the limits of all cosmologies and what we expect from them.

---------

Daniel Millet Gil holds a degree in Law from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a master's degree and a PhD in Buddhist Studies from the Centre for Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong. He received the Tung Lin Kok Yuen Award for excellence in Buddhist Studies (2018-2019). He is a regular editor and author of the web platform Buddhistdoor en Español, as well as founder and president of the Dharma-Gaia Foundation (FDG), a non-profit organization dedicated to the academic teaching and dissemination of Buddhism in Spanish-speaking countries. This foundation also promotes and sponsors the Buddhist Film Festival of Catalonia. In addition, Millet serves as co-director of the Buddhist Studies program of the Fundació Universitat Rovira i Virgili (FURV), a joint initiative between the FDG and the FURV. In the publishing field, he directs both Editorial Dharma-Gaia and Editorial Unalome. He has published numerous articles and essays in academic and popularization journals, which are available in his Academia.edu profile: https://hku-hk.academia.edu/DanielMillet