Introduction

Buddhism offers a path to liberation from the wheel of deaths and births that follow one another in a seemingly endless sequence. The Buddha had stated that his teachings were directed towards four groups: laywomen, nuns, laymen and monks. He never denied the ability of women to attain enlightenment and the elevated state of arahant consciousness. Nor did he refuse to teach them the Dharma. However, the admission of women into the monastic community was neither immediate nor without obstacles.

It will be difficult to know with complete certainty which texts or portions of texts reflect what the Buddha actually said and what was later interspersed by misogynistic scribes. Nor can one expect total coincidence in the texts available today about the women and men who were the protagonists and managers of Buddhism, but one can find accounts that reflect how certain events were perceived and valued in the times in which they occurred. Taking into account the above, the main contribution of Mahāprajāpatī, the foster mother of the Buddha Siddhartha Gáutama, in the expansion of the sangha or Buddhist community, will be briefly presented below.

Mahāprajāpatī, second wife of Suddhódhana

Siddhartha Gautama, who would later be known as the Buddha, was born as a prince of the Shakya clan in Kapilavastu, probably in the 6th century AD. He was the son of King Śuddhodana and Queen Mahamaya, who died seven days after giving birth to him. His sister Mahāprajāpatī took care of little Siddhartha.

Queen Mahamaya of the Sakyas clan was born into a kshátriya or ruling caste family in Devadaha, near the city of Kapilavastu where the Buddha was raised. He had six other sisters, including Mahāprajāpatī Gáutami. They both married King Śuddhodana of Kapilavastu and thus became his two chief queens, Mahamaya being the prevailing one. Queen Mahamaya gave birth to Siddhartha Gáutama, who would later be known as the Buddha and passed away a week later. Her sister Mahāprajāpatī took charge of the child Siddhartha and raised him as her own. He was not the only child she raised, for, as Sudhódhana's second wife, Mahāprajāpatī in turn had given birth to their daughter Sundarinanda and son Nanda, both of whom would eventually adopt the monastic life as would Siddhartha.

Mahāprajāpatī as a lay practitioner

We will skip the well-known story of Siddhartha's life as a young prince protected from the evils of life and his renunciation of the palace life at the age of twenty-nine, after learning of the existence of suffering in the world and committing himself to find a solution to it. We will also skip the six years he spent in the woods until he had an experience of enlightenment of consciousness in which he found the solution he was looking for.

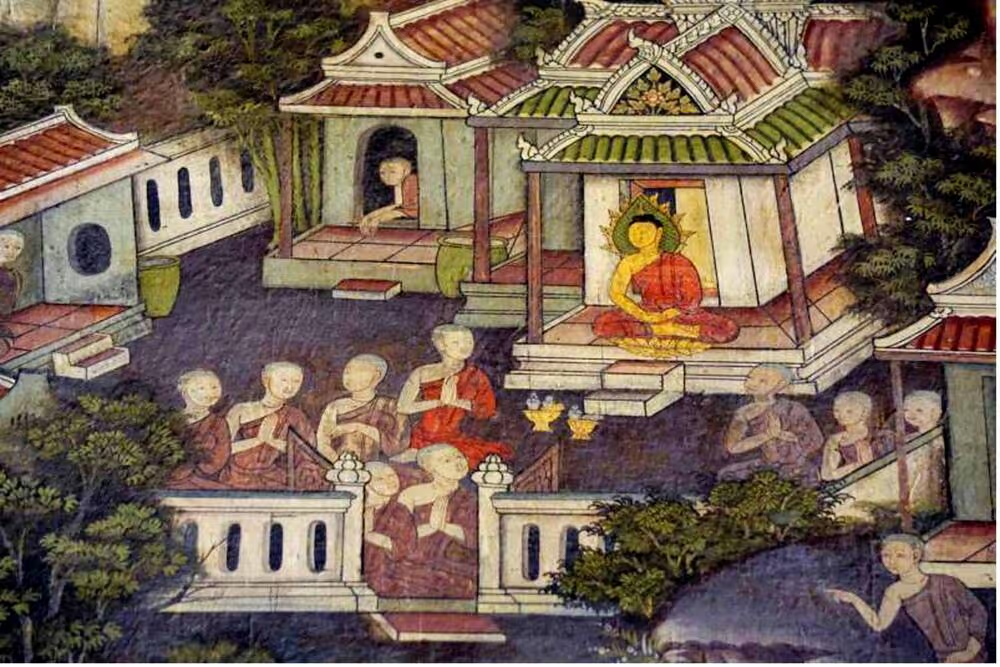

We will place ourselves approximately six years after the Buddha's enlightenment experience, that is, about twelve years after he left the palace and his life as a prince. The Buddha arrived at Kapilavastu with a group of five hundred (symbolic number to designate a large number) male followers and thus visited for the first time his father Śuddhodana, his mother Mahāprajāpatī, his chief wife Yashódara, his son Ráhula and other relatives and inhabitants of the palace where he had grown up.

The Buddha's relatives begged him in vain to become the prince of Kapilavastu again, as King Suddhódhana still had no heir to the throne. Instead, he devoted himself to preaching the Dharma to his relatives and other inhabitants of the kingdom, and they became his first lay disciples. Mahāprajāpatī succeeded in penetrating to such a depth in the teachings that she attained a first level of enlightenment of consciousness called sotapanna. (She would later attain the more advanced stages of sakadagami, anagami and arahant). Thus, she became the first woman in Kapilavastu to become a laywoman follower of the Buddha. Many men in the region were attracted to the Buddha's teaching and seized the opportunity. Inspired by their queen becoming a disciple of her son, the women of the palace also expressed their desire to learn the Dharma that their husbands and sons were receiving. Through the intercession of Mahāprajāpatī, the Buddha agreed to give them instruction and the women soon swelled the ranks of the lay sangha.

Mahāprajāpatī as a monastic practitioner.

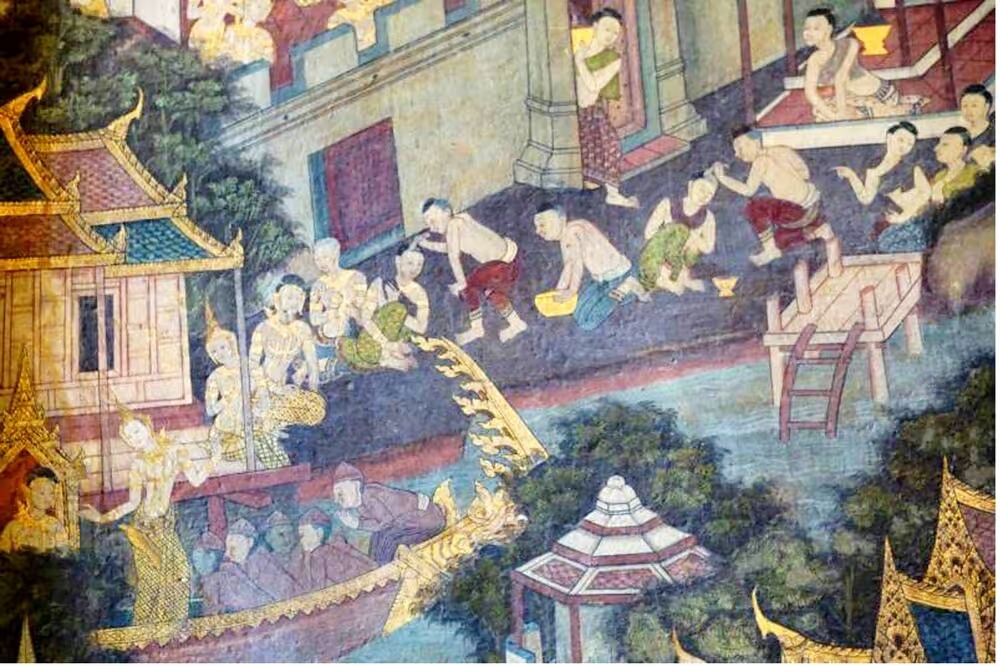

The Buddha made a second visit to Kapilavastu five years after his first visit, that is, seventeen years after renouncing his life as a prince. His father had passed away without leaving an heir. Siddhartha's decision to renounce the throne of Kapilavastu at the age of twenty-nine had caused commotion and disturbance, not only in the family but also in the political and social spheres of the kingdom. Since his departure, little by little, hundreds of Sakya men left their homes in Kapilavastu to become monks under the Buddha's leadership. The city would become vulnerable to foreign conquest, which would eventually happen with the invasion of the nearby kingdom of Kosala. Many women of the palace, both royal family and concubines and maidservants were in a state akin to widowhood, as their respective husbands had joined the Buddha's order. Several, including Mahāprajāpatī, had sons who in turn had become monks.

For the lay women of Kapilavastu, it was no longer a realistic option to continue their former lives as lay women, now without husbands. They had acquired a status akin to widowhood, without the traditional patriarchal social and legal structures that once would have afforded them protection. The Sangha, or group of followers of the Buddha, may well have served as a way to obtain protection similar to that of traditional family life, which was no longer available to them. They decided, therefore, to ordain as nuns in the Dharma, even though, as they had a few years earlier, they had a sincere desire to deepen the teachings that the Buddha had imparted to them during his first visit to Kapilavastu. They again asked their newly widowed queen Mahāprajāpatī for support and leadership to intercede on their behalf, who would not only give them the requested support but would join with them in requesting monastic ordination.

Mahāprajāpatī asked the Buddha for permission to be ordained, on behalf of herself and the other laywomen. Upon the Buddha's first refusal, Mahāprajāpatī submitted her request twice more and the Buddha again denied permission, i.e., a total of three times. As an alternative, he suggested that women lead a life of renunciation and Dharma practice within their own homes, a difficult situation for women whose husbands had abandoned home life.

There are several possible reasons why the Buddha initially refused to accept a female monastic order, but one stands out. Since celibacy was a requirement for a monastic life, perhaps he was concerned that such a requirement would be transgressed: most female followers of Mahāprajāpatī had ex-husbands who had become monks, and this circumstance might prove tempting for ex-partners to rejoin. The Buddha was always concerned to keep the female and male sectors separate, as the Sangha had to maintain exemplary behavior before their noble benefactors who, among other supports in exchange for receiving teachings, lent their palaces to the monks where they stayed during the rainy seasons.

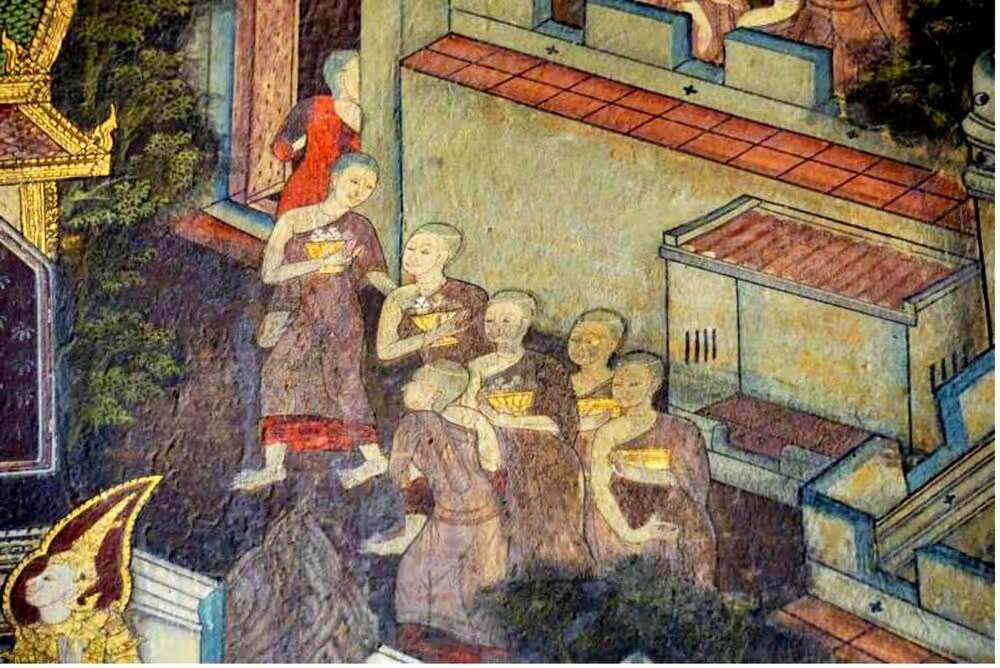

By this time Mahāprajāpatī already had five hundred female lay followers, a symbolic number as noted above. Neither Mahāprajāpatī nor his female followers were discouraged by the Buddha's three refusals: they shaved their heads, wore simple robes, and undertook a long and difficult journey on foot from Kapilavastu to Vaishali to obtain permission for ordination.

They traveled more than four hundred kilometers to meet the Buddha with his male sangha. Ananda, a relative and attendant of the Buddha, observed them after their long journey and asked them why they had undertaken such a long and arduous journey. Mahāprajāpatī explained to him that they had asked the Buddha three times in vain for permission to enter the monastic order. Ananda decided to intercede for the women and thus made three reminders to the Buddha: (1) that previous buddhas had ordained women, (2) that women had the same spiritual capacity as men to become arahants, (3) that his mother Mahāprajāpatī had raised and cared for him and thus the Buddha owed her an inescapable debt.

Inclusion of women as nuns in the sangha

(A) The set of eight rules

The Buddha eventually accepted the inclusion of women in the monastic order, albeit under certain conditions. The Buddha is credited with pronouncing a set of eight rules called gurudharma to be followed by nuns. The following is a translation of these rules as written in English by Ann Heirman:

(1) Even if a nun has a hundred years of monastic training, she should stand and bow before a newly ordained monk.

(2) A nun may not reprimand a monk by telling him that he has committed a fault.

(3) A nun may not chastise or admonish a monk, but a monk may admonish a nun.

(4) After having undergone a probationary period of two years, the ordination of a nun shall be celebrated in both the female and male orders.

(5) If a nun has committed a fault that merits temporary exclusion, she shall perform penance in both the female and male orders.

(6) Every two weeks, the nuns should ask the monks for instruction.

(7) The nuns are not allowed to spend the rainy season retreats during the summer in places where there are no monks.

(8) At the end of the rainy season retreat, each nun should participate in a ceremony in which the other nuns and monks are invited to point out the faults she has committed, whether seen, heard or suspected.

The eight rules may well have been a way of mitigating in advance an opposition to the inclusion of women in the monastic order by the male community, which would be a reflection of the misogynistic beliefs of the time in India and not peculiar to Buddhism. Given the patriarchal culture and institutions surrounding the Buddha, he somehow had to ensure that the monks would accept the inclusion of nuns. However, as much as the Buddha may have thought it prudent to yield some ground to the customs of his time, these rules are clearly discriminatory in our contemporary eyes.

(B) The future of the dharma

In addition to the set of eight rules, the Buddha is also credited with a prophetic comment about the future of the Dharma should women be accepted into the monastic order. The Buddha had told Ananda that the Dharma would have lasted a thousand years, but since women would now receive their monastic ordination, the Dharma would only last five hundred years, since the female presence would be like a plague ravaging a crop. In other words, the number of years the teachings would last would be cut in half.

At first glance, it might appear to be a derogatory commentary on the presence of women in the monastic order. Taken literally, it attributes to the Buddha a prediction that obviously has not been fulfilled. However, there are other ways to interpret these proclamations attributed to the Buddha. Sulak Sivaraksa states that through the establishment of the women's order, it would take only half as many years to entrench the Dharma in the world. That is, by doubling the number of followers of the Buddha, only half the time would be required to transmit the Dharma for several generations and in different lands.

In support of Sivaraksa's interpretation, it should be remembered that according to Buddhism, everything inevitably changes. A cultivated field would sooner or later become barren and, of course, a plague would accelerate its transformation. There are no fixed and eternal essences; even the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama Buddha of the present age are not permanent. By setting a probably symbolic period of five hundred years, i.e., half a thousand years, the Buddha was perhaps affirming that the Dharma he taught would not last forever either. Similarly, the teachings of the previous Buddhas were not eternal, as each Buddha had to adapt his teachings to the spaces and times of his respective era. In this way, the goal that the Buddha had set for himself-to have as many beings as possible attain enlightenment-would accelerate with the doubling of the number of followers.

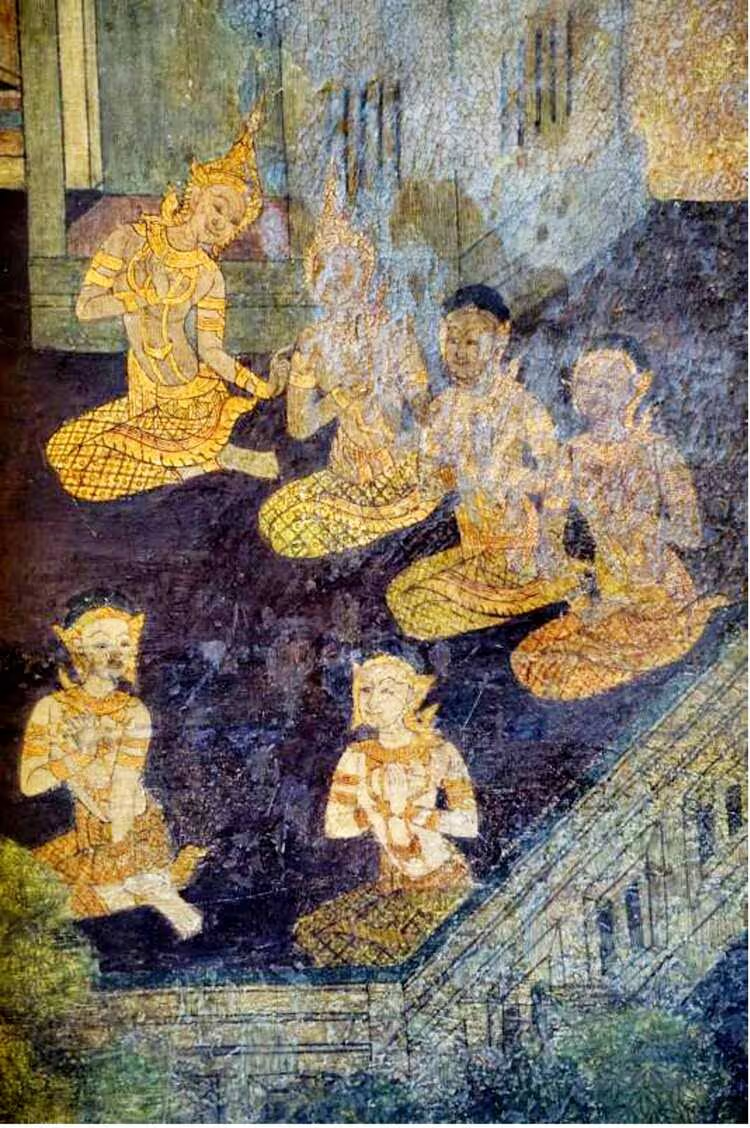

As the Buddha gave his approval for women to enter the monastic community, Mahāprajāpatī became the leader and mother figure for both nuns and laywomen. It is said that Mahāprajāpatī lived a very long life; there even came a time when she went to the Buddha well advanced in age to tell him that it was right for a mother to predecease her children. The Buddha assented and so, a few months before the parinirvana or death of her son, Mahāprajāpatī was the first female disciple to enter the state of nirvana upon her passing. It is also said that, of their own accord, her five hundred female followers also attained nirvana by passing away on the same day as their teacher.

Conclusions

As Sivaraksa rightly points out, both Mahāprajāpatī Gótami and her five hundred female followers were completely certain that, like men, they had the capacity to become arahants and so they did not falter in their insistence on belonging to the monastic order established by the Buddha. In this sense, Mahāprajāpatī and the first order of nuns are an example of tenacity in the Dharma.

The Buddha had stated that his teachings were directed toward four groups: laywomen, nuns, laymen and monks. Mahāprajāpatī played an essential role in making these four groups of people part of his sangha or community of followers. Since Buddhism has gone around the world and is present on every continent today, it can be inferred that the female participation of laywomen and nuns significantly increased the presence of Buddhism. Indeed, Mahāprajāpatī doubled the number of followers of the Buddha and opened the doors of the Dharma to as many women as wanted to learn and practice it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY .

Anālayo, Bhikkhu (2013). The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sāsana. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 20, 110-193. Available at https://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2013/06/Anaalayo-bhikkhuni-revival1.pdf

Anālayo, Bhikkhu (2022). Daughters of the Buddha: Teachings by Ancient Indian Women. Somerville, Massachusetts, USA: Wisdom.

Garling, W. (2016). Stars at Dawn: Forgotten Stories of Women in the Buddha's Life. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Shambhala.

Garling, W. (2021). The Woman Who Raised the Buddha: The Extraordinary Life of Mahaprajapati. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Shambhala.

Heirman, A. (2011). Buddhist Nuns: Between Past and Present. Numen 58, 603-631. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/55700974.pdf

Ohnuma, R. (2006). Debt to the mother: A Neglected Aspect of the Founding of the Buddhist Nuns' Order. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 74, 861-901. Available at https://www.academia.edu/10975640/Debt_to_the_Mother_A_Neglected_Aspect_of_the_Founding_of_the_Buddhist_Nuns_Order

Ríos, M. E. (2017), Aesthetics of abandonment: the retreat of Buddhist nuns. Ἰlu. Journal of the Sciences of Religions 22, 343-357. Available at https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ILUR/article/view/57420/51724

Sivaraksa, S. (1992). Seeds of Peace: A Buddhist Vision for Renewing Society. Berkeley, California, USA: Parallax. Available at https://archive.org/details/seedsofpeacebudd00sula

Katherine V. Masís-Iverson

The author is a retired professor from the University of Costa Rica in San José, Costa Rica. For several years as an active teacher, she taught introductory courses in philosophy at the School of General Studies, as well as courses in ethics and Hindu and Buddhist thought at the School of Philosophy of that institution. Some of her work can be found at https://ucr.academia.edu/KatherineMas%C3%ADsIverson