Zenfor Nothing What does this mean? According to Antai-ji-the Japanese sōtō zen monastery where the movie Zen for Nothing was filmed- zazen ("sitting meditation"), if practiced solely for the purpose of zazen, is good for nothing! But only if it is done well! But "nothing" is important. What is nothing? Nothing is nothing, emptiness, a voidness. An ensō. mu! You have to experience it, not just know it. zen is nothingness? It is an experience. What is zen? It is reaching your true nature, before thinking, your buddha nature, which must be experienced, not just understood. In the same way, the movie, Zen for nothing, has to be experienced, not just seen or learned from this review. But everyone can experience the film, not just followers of Zen Buddhism. All that is required is interest and willingness. The film is available on DVD, with subtitles in English, German and French.

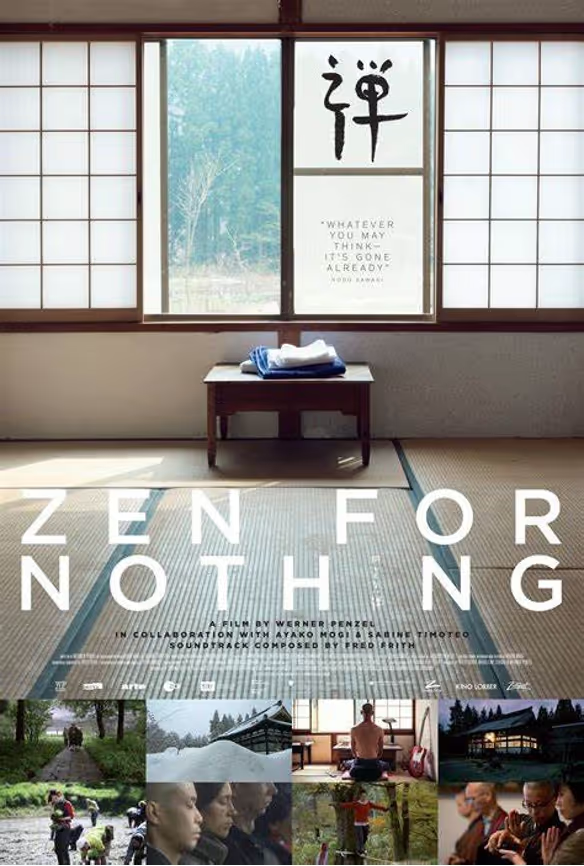

Zen for Nothing is a German-Swiss film, released in 2016 and excellently directed and filmed by German film director Werner Penzel, with an atmospheric and innovative soundtrack by English multi-instrumentalist and composer Fred Frith. The film is about the experience of a Swiss actress and dancer, Sabine Timoteo, who spent part of the fall, winter and spring of 2014/2015 living and working as a lay practitioner in a Zen sōtō monastery in Japan. Zen for Nothing, 100 minutes long, is described as a documentary, but it is not a documentary in the conventional sense, as there is no narration as such, just the sounds of Sabine and others talking, of silences, of chanting, of Buddhist percussion instruments and other sounds, natural and artificial.and, of course, also images, of movement and stillness, in and around the monastery and elsewhere.

Chan Buddhism is the origin of Zen Buddhism. The sōtō and rinzai Zen Buddhist schools of Japan, the sŏn Buddhism of Korea, and the thiền Buddhism of Vietnam developed from Chan Buddhism, a form of Chinese Buddhism that is a fusion of Indian dhyāna Buddhism and Chinese Taoism. All these schools of Buddhism are essentially the same in their principles, although different in their practices. Simplistically, all can be described as "Zen Buddhism."

The film Zen for Nothing was filmed at Antai-ji, a small Zen sōtō monastery in the forested hills of northern Hyōgo Province in western Japan, overlooking the Sea of Japan. Antai-ji was originally founded in 1921 in Kyōto, but moved to Hyōgo Province in 1976. The shrine is known for its study of the Dharma, its practice of zazen, in particular, shikantaza ("just sitting") and, unusually these days, takuhatsu (formal begging for alms, with bowls, wearing traditional medieval Japanese robes, large straw hats and straw rope sandals). Despite receiving donations, Antai-ji is largely self-sufficient. "A day without work is a day without food" (Baizhang Huaihai, Chan master of the Tang dynasty).

This contrasts with many Japanese monasteries and temples, whose income is largely derived from conducting funerals. Antai-ji is both traditional and modern, following strict monastic routines and practices and a hierarchy, but with monastic and lay practitioners, men and women, both Japanese and non-Japanese, living, working and practicing together as equals. At the time of the film's shooting, the abbot of the monastery was a German monk, Muho Nölke, the ninth and first non-Japanese abbot, who was succeeded by a Japanese nun, Ekō Nakamura, as the current and first female abbot.Going back in time, the fifth abbot was the eminent 20th-century Zen master of sōtō, Kōdō Sawaki, famous for bringing Zen practice into the lives of ordinary people; some of his teachings are quoted in the film, "Everything begins when we say "I." Everything that follows is an illusion" (Kōdō Sawaki, quoted at the beginning of the film).

The film Zen for Nothing begins with a night shot of Antai-ji, then moves indoors, where a large Buddhist drum and metal soundboard are beaten, followed by a brief chant in Japanese. This sets the stage for the film. We then meet a young European girl, the protagonist, Sabine Timoteo, who travels train through a large industrialized Japanese city, changes trains, takes time to smoke a cigarette on a station platform while waiting, and then on another train into the countryside along the coast and hills.Finally, we see her walking up a steep country road, carrying a large backpack, then up an even steeper flight of stone steps, with fallen leaves and browns visible, suggesting early autumn, and into the grounds of the shrine, Antai-ji.

Sabine takes off her boots, enters the monastery building and meets a young American, a lay practitioner, who shows her around the compound and explains some of the basic rituals and practices she would need for her stay there, such as bowing and gasshō ("putting her palms together"). From then on, he learns things largely by example, following what others do. He does not wear robes, as do the other lay practitioners; only the monks wear robes, but not when working in the monastery and its grounds, where, including the abbot, they are largely indistinguishable from the lay members of the Sangha community, except for their shaved heads.

Night. Darkness. Silence. Then early morning. Still dark. And silent. A bell rings. Time for the first zazen session of the day, before breakfast. Meanwhile, breakfast is being prepared in the kitchen by practitioners, who are on duty for breakfast that day. The time on the kitchen clock is 4.05 am. The others meditate, sōtō zen style, in front of the zen-dō ("meditation hall") wall. The abbot patrols the seated meditators.He uses the kyōsaku ("awakening stick") to deliver blows to the back of the shoulders, two blows to each shoulder, of those whose posture is bad, or who are falling asleep. The meditator and the abbot bow to each other before and after the strokes. Postural correction and muscular relief.

A bell rings. End of meditation. Chanting follows. Then breakfast. The time on the kitchen clock is 6:07 a.m. A bell rings. The practitioners enter the dining room and, once seated, chant briefly and make an offering of rice to the Buddha before eating. Breakfast is eaten in silence and a food and bowl protocol is strictly followed. Sabine learns by observing others. Dawn breaks and there is an autumnal morning mist. More zazen. Heavy rains. The karesansui (Japanese Zen garden) floods. But it will dry out and be redone. No problem! A beetle walks across the tatami mat in the zen-do. No one pays any attention to it. Outside, seen through the shoji (traditional Japanese paper windows/walls),the sun has begun to shine. A bell rings. This morning zazen session is over. The participants leave the zen-do and go outdoors to begin their work for the day in and around the monastery and its grounds. As instructed by master Chan Baizhang.

Outside, we hear conversations for the first time since the lights went out the night before. During more than 20 minutes of film, no dialogue is heard, only natural and artificial sounds. Sabine and a monk talk about life. Then it's time for work. Including washing vegetables outdoors and preparing food in the kitchen indoors. Then eating.This is the midday meal, I suppose, since strict Zen practice is usually to refrain from eating after noon. Evening comes. You see monks and lay people showering in community. You see nuns and laywomen chatting on their futons on the tatami-covered floor of their dormitory. Lights off.

It's morning again. Another autumn morning fog. Daily morning chores are performed, such as scrubbing the floors of the dwelling. A monk briefs the participants on the day's work tasks. Buildings must be repaired and maintained. Trees must be felled, sawed into pieces and cut for firewood. Brush must be cleared for planting rice. Chickens must be fed (for their eggs, I suppose, since Zen Buddhists are vegetarians). It is time for the midday meal. Chanting before and after the meal. Time for chatting. Then more work. Sabine reads a book of Zen poems in German.

Now winter has come! Snow covers the ground and the monastery buildings. Monastic and domestic routines continue. But relaxation is also important. A picnic in the snow on the hills above the monastery. Food, pots, utensils, bowls and chopsticks are carried uphill by some of the practitioners on snowshoes. Bonfires are lit. What looks like a bottle of sake is heated in a pot. A non-alcoholic type, I suppose, since the consumption of alcoholic beverages is contrary to the fifth precept.

As long as you say that zazen meditation is something useful, something is not quite right. Zazen is nothing special.... You want to become a buddha? What a waste of energy! Now is simply now. It is simply you (Kōdō Sawaki).

The practitioners share their thoughts and experiences of life at Antai-ji. Sabine is moved to tears as she quotes a French poem, "Painting the Portrait of a Bird," by Jacques Prévert, in which she compares the bird cage painted in the poem to a frame. At first she felt that everything related to monastic life was enclosed within frames, which frightened her. But gradually she became less frightened and began to like them. Now she treasures her experiences in the monastery.

The snow on the ground is melting. Green shoots and leaves - spring is here! Rice is planted. Bamboo shoots are harvested. The karesansui is rebuilt. Shrine buildings are repaired and maintained. Life at Antai-ji comes back to life after a long, cold winter.

Sabine has an interview with Abbot Nölke, but not in the formal Japanese rinzai zen or Korean sŏn style, with kōans, but an informal chat in German and she tells him how she felt protected and in good hands during her stay at Antai-ji.

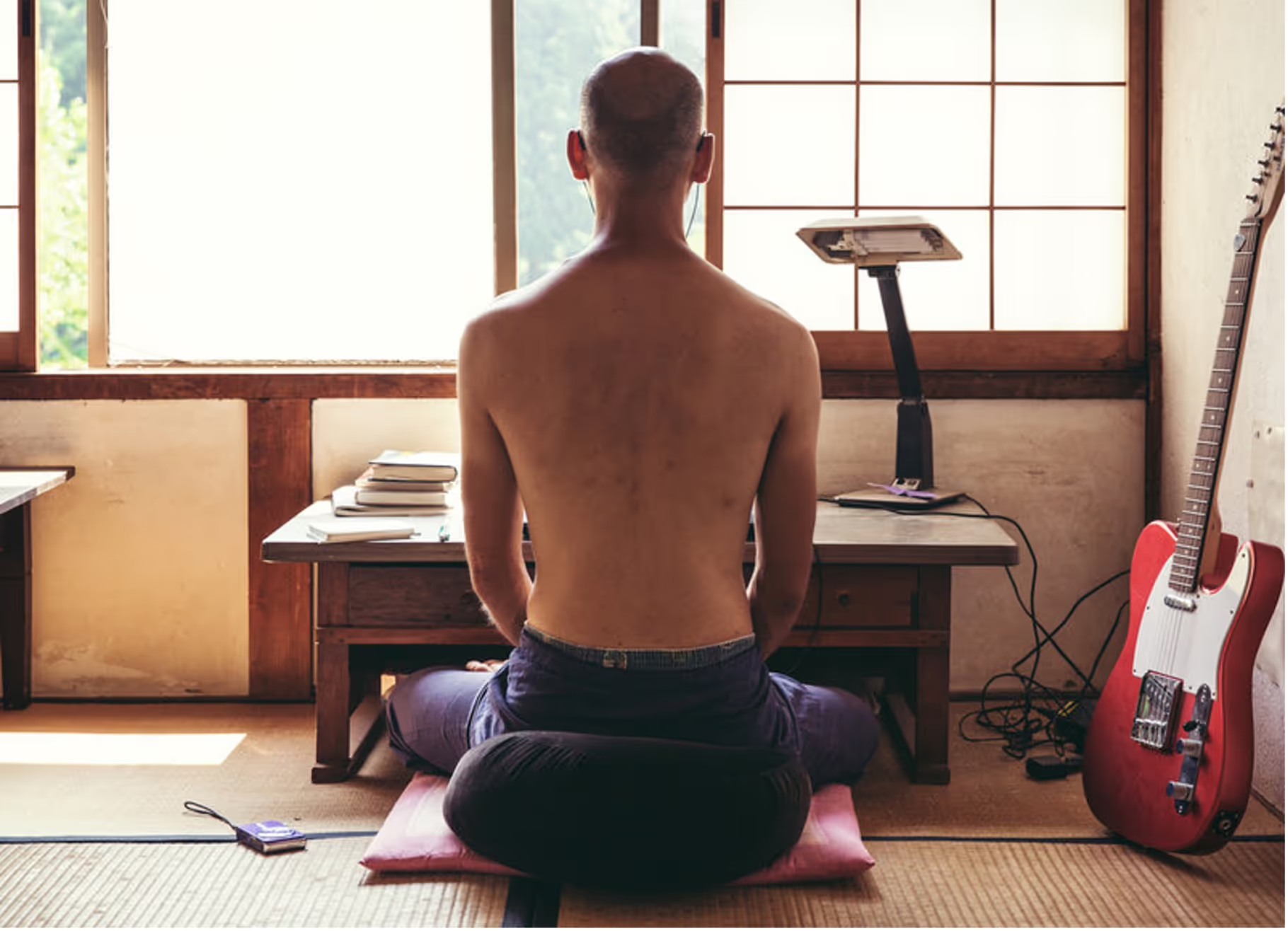

Dead branches are cleared from the monastery grounds. A bonfire is lit. A picnic is held, with what looks like beer. Non-alcoholic beer, I suppose. Rock music is played by some of the practitioners! Electric and acoustic guitars, and various percussion instruments. sukha?

The next morning, Sabine shaves the head of a Japanese lay practitioner she has befriended at Antai-ji, Ekō Nakamura, who has decided to become a nun (she succeeded Abbot Nölke as abbot five years later). The abbot informs the practitioners about the takuhatsu and tells them that they will leave for Osaka the next day to beg for alms. A group of monks, led by the abbot and including Ekō Nakamura, now dressed as a nun, descend the stone steps of the monastery, with Sabine trailing behind, her large backpack on her back. Her time at Antai-ji has come to an end. In Osaka she bids farewell to the monks and nuns and boards a train. The monks begin their alms rounds in the streets of the city.

"When you are dreaming, notice it is clear that you are dreaming.... Wandering inside your own illusions means living your life like a sleepwalker" (Kōdō Sawaki).

And so the film ends.

Zen for Nothing is a wonderful, beautiful, happy and evocative documentary about life in a Zen sōtō monastery in Japan. Highly recommended.