This item is part of our special edition: “Deciphering Chinese Buddhism”

You can read the previous article in this series by clicking here

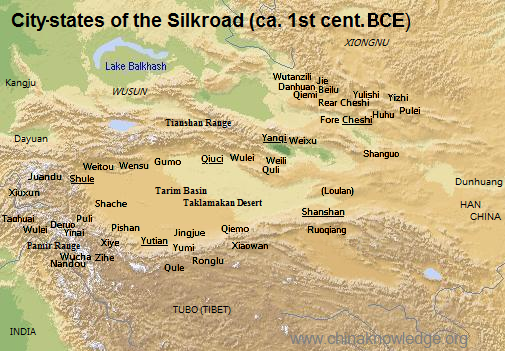

Buddhism entered China through the deserts of the Tarim Basin, in caravans that crossed these arid regions, carrying not only silk and spices, but also the seeds of enlightenment. The most accepted theory places its arrival at the beginning of the 1st century CE, during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25—220). The evidence points to a gradual introduction through the Silk Road, rather than a direct spread from India. But it was not the only route: there were maritime routes from Southeast Asia to the ports of southern China, a topic that we will discuss another time. In this one, we will explore why the Silk Road became a privileged route and how Dharma served as a bridge between cultures.

Four main factors —historical, military, cultural and spiritual— explain the arrival of Buddhism to China in the first century C.E., specifically through the Silk Road: 1) the presence of Buddhism in Central Asia, coming from Gandhāra and Bactria, where a rich tradition had already been consolidated; 2) the political, military and cultural dominance that the Han dynasty exercised over commercial roads in that period; 3) the strategic importance and commercial dynamism of this network of routes; 4) a context of spiritual crisis and the search for values in China, particularly towards the end of the Han Dynasty. In this first part of the article, we'll explore the first two factors, leaving the rest for the next one.

The presence of Buddhism in Central Asia

The spread of Buddhism to the north and east from India took place through several commercial and pilgrimage routes that linked the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia. In ancient Chinese literature, this region was called “Western Region” () and encompassed Parthia (), the territory of the Yuezhi (), forerunners of the Kushan Empire; Sogdiana (), related to Kangju (); in addition to Hotan () and Kucha (). With Bactria, Gandhāra, Margiana and Ferghana —in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, northwestern China and Iran—this region was the scene of a series of centers where Buddhism took root, was translated, interpreted and reinterpreted before it arrived in China. It can be said that these centers functioned as synthesis laboratories, where multiple spiritual traditions came together to give rise to new ways of understanding and communicating the teachings of Buddhism.

During the first centuries of our era, numerous translators and Buddhist monks from these kingdoms and territories of Central Asia visited China, contributing to the spread of this religion and to the cultural and intellectual exchange between the two regions. This hard work of translation and exegesis was crucial for consolidating Buddhism as one of China's main religions, as well as for its subsequent development in forms adapted to the Chinese context.

This process of diffusion in Central Asia, according to tradition, was initially promoted by the emperor Aśoka of the Mauryan dynasty in the 3rd century BC, after the “Third Buddhist Council”, held in 250 BC in Pāthaliputra (now Patna, India). According to Sinhalese chronicles, Aśoka would have promoted faith beyond the borders of his kingdom through nine diplomatic and religious missions, with regions in the northwest such as Gandhāra and Bactria standing out (Mahāvashsa, chapter XII; Dipavasa, chapter VIII). Although its historical scope is subject to debate, this narrative reflects early transregional connections.

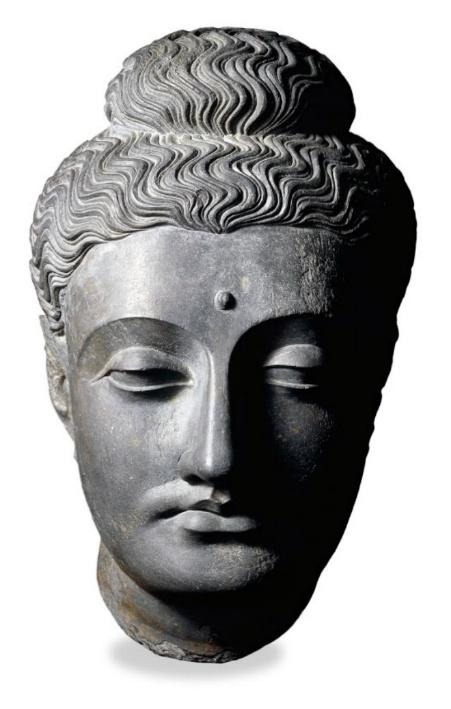

Bactria (north of present-day Afghanistan) became a turning point in the 3rd-2nd centuries BC due to its strategic position on the Silk Road. During the Greco-Bactrian era, the reign of Menander I (Milinda) crystallized, through the Milindapañha, the dialogue between Greek thought and Buddhism. Also, in the artistic field, Bactria, together with the center of Mathurā, played a key role in introducing the anthropomorphic image of the Buddha, which displaced aniconic patterns. Its monasteries, especially those of Balkh, stood out as important centers of translation and teaching. After the conquest by the Yuezhi in the 2nd century BC, the region was integrated into the Kushan Empire, maintaining its role as a crossroads of Hellenistic and Buddhist influences.

Gandhara (northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan) was an important focus between the 3rd century BC and the 5th century AD, where Indian, Greek and Persian traditions converged. His art elevated Buddhist iconography by merging naturalism and Hellenistic draping with the figure of the Buddha, leaving a lasting imprint on Asia. The birch bark manuscripts of Gandhāra are among the oldest Buddhist testimonies, and evidence doctrinal and linguistic plurality in early Buddhism.

Sogdiana (now Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) articulated trade and religion through translation networks and cultural intermediation. In Chinese sources, the “Kang” clan () is linked to Sogdian origins. Intellectuals and translators such as Kang Ju, Kang Menxian, Kang Shenkai and Dharmasatya excelled in the reinterpretation and dissemination of texts, while Sogdian commercial projection gained greater weight between the 4th and 7th centuries.

Margiana and Ferghana (Turkmenistan and Ferghana Valley) functioned as cultural corridors that facilitated the transit of religious, artistic and philosophical ideas. Ferghana, famous for “heavenly horses”, played a key role in the diplomacy and military capacity of the Han dynasty, reinforcing transregional exchanges.

Khotan, located in the Taklamakan desert, was an oasis that connected India with China and a meeting point between Chinese, Indian and Tibetan civilizations. During the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, Buddhism came to Khotan from the west under the influence of the Kushan Empire. Between the 7th and 10th centuries CE, Mahayana was consolidated in Khotan, as evidenced by manuscripts and translations into the local language. The Chinese monk Faxian described it as a thriving center with thousands of Mahayana monks. Among the translations into the local language, the Prajñāpāramitā (“The Perfection of Wisdom”), the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa (“The Teaching of Vimalakīriti”) and the Sukhavativyuha (“The Description of the Pure Land”). Figures such as Mokṣala, active in 291, contributed to the spread of Buddhism in China.

Kuqa (on the northern route of the Tarim) was one of the most influential oasis kingdoms. In the 3rd century CE, it housed Śrāvakayāna and Mahāyāna communities, with numerous monasteries and stupas. His most lasting legacy was his contribution to translation: tradition attributes around 300 versions to Kumārajīva, although modern catalogues recognize between 80 and 100 complete or partial translations, fundamental to the Chinese canon. Despite its decline towards the 8th century, due to political-military pressures, its cultural impact was profound and lasting.

For its part, Partia (in present-day Iran) acted as a cultural bridge between the Greek world and India, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas. From this region came An Shigao, a prince who renounced his rank to become a monk and who, between c. 148 and 180 CE, translated numerous texts into Chinese, standing out for his remarkable terminological adaptation. Along with An Xuan, he consolidated Parthia as a key intermediary in the expansion of Buddhism to the east.

As for Scythia, a vast region inhabited by nomadic peoples, its contribution was decisive between the 2nd and 4th centuries BC, thanks to translators such as Lokakṣema, Zhi Yao, Zhi Qian and Dharmarakṣa, who introduced and stabilized important doctrinal bodies in Chinese. Finally, from India —the cradle of Buddhism—, translators such as Zhu Foshuo, Dharmapāla and Dharmakāla (2nd-3rd centuries BC) brought the teachings directly to China, consolidating the transmission in their original tradition.

The Kushan Empire (or ”Cuchana”)

The Kushan Empire (30-375 BC) was central to the introduction of Buddhism to China, providing stability on the Silk Road and actively sponsoring religion. This multicultural empire reached its peak between 105 and 250 C.E., controlling a large part of the trade routes from Northern India and Afghanistan to Central Asia. Its cosmopolitan government was characterized by a remarkable openness to diverse religious and cultural traditions, which created ideal conditions for the spread of Buddhism. Under his administration, Buddhist monasteries flourished as centers of translation and study, while caravans carried not only merchandise, but sacred texts, ideas and Buddhist practices, allowing both Mahayana and some Nikaya schools to find fertile ground for expansion into China.

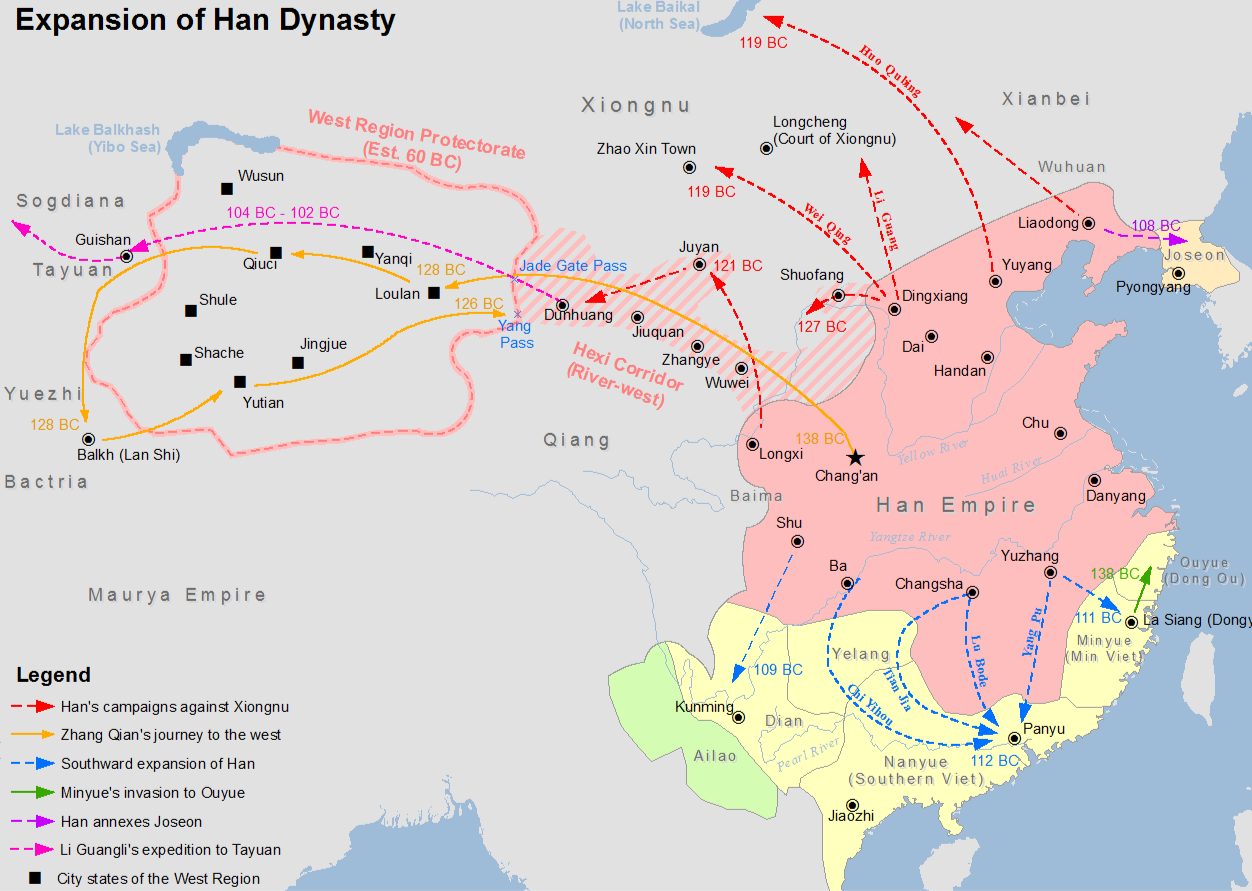

The Kushan Empire originated from the historical migration of the Yuezhi (yüeh-chi,/), a nomadic people who inhabited the steppes of the current province of Gansu, China, during the first millennium CE. Defeated by the Xiongnu in 176 BC, the Yuezhi were divided into two groups. The older Yuezhi migrated to the northwest, crossing the Ili Valley, Sogdia and reaching Bactria, where the Kushana tribe founded a key empire for the development of the Silk Road and the expansion of Buddhism to China. For their part, the smaller Yuezhi moved south, settling near the Tibetan plateau. Some integrated with the Qiang people in Qinghai, founded the city-state of Cumudana (now Kumul/Hami), or mixed with local populations. This migration not only transformed the political landscape of Central Asia, but it also boosted the exchange of technologies and knowledge between East and West.

During the reign of Kaniṣka I (approximately 127-151 CE), Buddhism experienced one of its moments of greatest expansion and development. The Sarvāstivāda tradition places in his reign a “Fourth Council” in Kashmir, an assembly that would have helped to systematize Buddhist texts and commentaries. Under his patronage, Gandhāra's art reached its peak. During this time, coins were minted with images of the Buddha and numerous monasteries and stupas were built, including the famous Peshawar stupa, which, according to Chinese sources, reached 120 meters in height. This period marked a decisive moment in the transformation of Buddhism from a regional religion to a transregional faith, which facilitated its integration into the cultural fabric of China.

The regions of Central Asia were not mere spaces of transit, but real fields of cultural experience in which Buddhism underwent profound transformations. Its strategic location at the intersection of Indian, Persian, Hellenistic and nomadic civilizations allowed for a rich exchange of religious ideas and practices. The Silk Road acted as a cultural nervous system through which merchants, traveling monks and ambassadors transported not only merchandise, but also art, philosophy and spirituality, turning Buddhist monasteries into centers of cosmopolitan knowledge. Figures such as Kumārajīva, although later, exemplify how these exchanges resulted in key translations from Sanskrit into Chinese, which enriched Buddhist doctrine.

Buddhist communities in Central Asia actively reinterpreted Buddhism, translating texts into local languages such as Sogdian, Bactrian and Khotanese. This process involved more than a literal translation: it involved a conceptual reworking that enriched the original doctrine. In Gandhāra, a unique artistic style was developed that merged Greco-Roman elements with Buddhist iconography, creating sculptures of the Buddha with westernizing features using Hellenistic techniques, which is a testimony to this extraordinary cultural synthesis. This adaptability was fundamental to preparing Buddhism for its expansion to China, where it would interact with Confucianism and Taoism, and would be transformed into its own forms, such as Chan (Zen) Buddhism.

II - The military, political and cultural dominance of the Silk Road in the 1st century CE

Since the beginning of the Han Dynasty, the empire faced a colossal geopolitical challenge: the Xiongnu confederation. These powerful horsemen and nomadic warriors from the steppes of northern China posed a constant threat to the empire's borders and stability. In addition, they blocked the Han dynasty's access to the coveted Western lands, thus hampering their territorial and commercial expansion.

It was Emperor Wu of the Han (141-87 B.C.E.) who understood that solving the question of the Xiongnu required a strategic perspective in multiple dimensions. His ambitious vision not only integrated the military domination of the region, but also a sophisticated network of diplomatic alliances and strategic negotiations with third states, programmed to weaken the Xiongnu dominance, defeat them and incorporating military confrontation, diplomacy and negotiations with third parties, with the objective of weakening their power and, thus, opening new trade routes that would transform the geographical politics of the region.

In 138 B.C.E., this strategy came to fruition with the sending of emissary Zhang Qian on a diplomatic mission that would prove to be a historic turning point. Although he initially failed to achieve the military alliance he sought and was captured and held by the Xiongnu for a decade, his expedition revealed a new geographic-cultural landscape. Zhang Qian returned to China after his extraordinary trip with valuable information for the Han court about the existence of very prosperous kingdoms in Central Asia, possible trade routes and strategic resources, including the coveted “heavenly horses” of Ferghana, which transformed Chinese understanding of the West and laid the foundations for future Han expansion.

Imperial policy materialized in the occupation of strategic territories. The Han ruled the Hexi corridor and the Tarim basin with great military and political force. They placed garrisons and forged alliances with local kingdoms. This expansion was not limited to a geographical conquest; it was conceived as a project of cultural and economic integration that would drastically modify the system of exchanges between East and West.

By the 1st century C.E., the Han Empire had already consolidated an area of unprecedented dominance over the Silk Road, transforming it from a simple commercial corridor into a complex system of political, economic and cultural exchange. Control extended beyond traditional geographical boundaries, establishing a network of influence that connected China to Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and western territories. The supremacy of the Han was manifested in a sophisticated infrastructure: a system of posts and military garrisons guaranteed the safety of the caravans. In addition, strategic control points were established in the Hexi corridor and the Tarim basin, allowing not only the protection of trade routes, but also the effective control of the flows of goods and people.

What had started out as a geopolitical need for containment gradually turned into a single exchange corridor. The Silk Road began to take shape, not only as a commercial path, but also as a conduit of profound cultural exchange. Traders from different regions traveled these routes, transporting not only goods, but also ideas and cultural practices.

Beyond trade, the Han promoted a remarkable strategy of cultural integration. Buddhism began to penetrate Chinese society, introducing new philosophical and spiritual perspectives. Artists, monks and merchants from different regions not only traveled the routes, but also settled down, creating a unique cultural mix.

Bibliography

1. Benjamin, Craig (2007). “The Yuezhi: Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria”. Brepols, Turnhout.

2. Foltz, Richard (2010). “Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization”. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

3. Hansen, Valerie (2012). “The Silk Road: A New History”. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

4. Lamotte, Etienne (1988). “History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the Saka Era”. Peeters Publishers, Leuven.

5. Liu, Xinru (2010). “The Silk Road in World History”. Oxford University Press, New York.

6. Thapar, Romila (2002). “Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas”. Oxford University Press, Delhi.

7. Zürcher, Erik (2007). “The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China”. Brill, Leiden.

8. Salomon, Richard (2018). “The Buddhist Literature of Ancient Gandhāra”. Wisdom, Boston.

9. Rong, Xinjiang (2013). “Land Routes of the Silk Road in the Han to Tang Periods”, in Susan Whitfield (ed.), “The Silk Road”. British Library, London.

You can read the second part of this article by clicking here